I don’t recall if my book included the scene at the court of the King of Calicut where da Gama cut a ludicrous figure by offering this wealthy Asian potentate Portuguese goods of little worth. The four cloaks of scarlet cloth and the six hats, along with the other trivial gifts (did the great king really need a cask of Portuguese honey?) failed to impress.

I can say, however, that my book did not tell me about the sinking of the Miri. This occurred during da Gama’s 1502 visit to the Indian Ocean. The Miri was a merchant ship carrying cargo and passengers, many of them pilgrims bound for Mecca. They never made it. When da Gama overtook them they promptly surrendered, assuming they would simply pay a ransom to these pirates before being released. Da Gama deprived them of their wealth, in due piratical form, but what followed was pure terrorism. Da Gama burned the Miri and the men, women and children who were in it. Even at a 500-year remove it is a ghastly story to read.

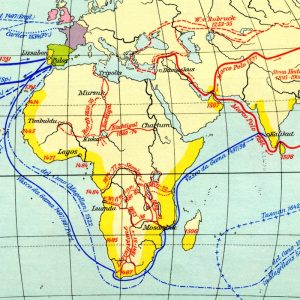

Why did da Gama commit this atrocity? The motive was a hatred of Muslims. Portugal was at the time in continuous conflict with Muslim Morocco. The Portuguese had taken the rich entrepôt city of Ceuta from the Arabs in 1415 and thereby acquired a taste for oriental trade. Unfortunately, the source of this trade was in the hands of the detested followers of Muhammad. It was to avoid these pernicious middlemen that the Portuguese sailed around Africa. That and the beguiling prospect of being able to attack Mecca from the Red Sea and from there march on Jerusalem. Booty and salvation awaited.

The sinking of the Miri was not the only massacre committed by the Portuguese in their conquests around the Indian Ocean. They had the most powerful artillery in the East at that time and they made ruthless use of this technological advantage. Although they failed to attack Mecca and got nowhere near Jerusalem, the extensive African and Asian empire they did win lasted well into the 20th century.

All this I learned from Roger Crowley’s Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire. I read this excellent history before my recent visit to Lisbon.

It was hard to avoid Vasco da Gama in Portugal’s capital; the city celebrates the terrorist at every turn. His name adorns a bridge, a ship, a tower, a shopping centre, a cinema, a villa, a functions room at the Four Seasons, an aquarium, a pharmacy, a dental practice, three restaurants, a Pizza Hut, a garden, two avenues, a street and various monuments.

The grandest of these last is the edifice built in 1960 by the Salazar dictatorship, officially called the Discoveries Monument, but widely known as the Vasco da Gama monument. It is decorated with giant sculptures of the heroes of the age of exploration. Da Gama is in the third row behind Henry the Navigator and King Afonso V. I count thirteen stone swords and six stone crosses which seems a fair summary of the mix of piety and brutality with which the Portuguese went about their discovering.

Not far away is Vasco da Gama’s tomb, in the Church of Santa Maria. A stone effigy of da Gama lies atop the sarcophagus; he is praying, his sword is at his side.

Around the corner from da Gama’s last resting place there is the Maritime Museum. It is wonderful, at least if you enjoy models of ships as much as I do. Naturally it covers the voyages of da Gama and his fellow conquistadores. Caravels, carracks, carronades and swivel guns, lateen and square rigged, maps, astrolabes and armillary spheres, monsoons and Cape storms, it is all there. Oddly enough, there is no mention of massacres, no display of the unfortunate Muslims aboard the Miri being burned alive.

The museum is organised in chronological order. Thus, in the last of the halls, I find the story of Portugal’s 20th-century colonial wars. I learn of the sailors who died when their ship was bombarded by the Indian Navy in the brief tussle over Goa. I see photographs of marines going up African rivers in rubber boats. Some nice models of gunboats too. I am told the mission was to protect the Portuguese settlers and the native population. Nothing to do with suppressing a native rebellion apparently.

My visit ended with afternoon tea at the museum’s café and bookshop. Crowley’s book was available I was happy to see. The orange cake was delicious. The shop was modern and offered free wifi. The code was easy to remember, just type in ‘vascodagama’.